Tags

I was predisposed to regard Lynsey Hanley’s book favourably, having very much enjoyed her previous work, Estates, and finding that we had a similar background, albeit separated by a decade or so. While Hanley was raised on the Chelmsley Wood council estate in Solihull, I was fortunate enough to grow up in the slightly more salubrious Shirley: my parents were both born into poverty but benefited from postwar employment levels, so that by the time I was born my father had been promoted to foreman in the factory where he worked, enabling my mother to work only part time and the pair of them to take out a mortgage on a house beyond the boundary of Birmingham itself, albeit only barely. The similar backgrounds and biographies are germane to my enjoyment of Hanley’s book, not because they generate a sense of solidarity or recognition, or not only because of that, but also because they go some way to explaining our mutual interest in sociology and our fascination with the issue of class.

Whereas Hanley recounts discovering the middle class for the first time at Solihull Sixth Form College, my first encounter took place at a younger age, 14, when I joined the local tennis club. It was there that I first met not just the middle class but also snobbery, as well as contempt, and disdain, both for me and for ‘my people’. Having been fortuitous and privileged up to that point, it was not until my teenage years that I became conscious of not being good enough, of being observed from the outside and judged negatively, as wanting. It was at this point that class became for me a reality, a lived experience. When I subsequently moved to Manchester and found sociology was an A level subject on the local college curriculum, I took to it like a duck to water.

It was sociology that allowed me – and Hanley – to make sense not just of our place in the world but also of the world itself. And this brings me to the most striking revelation I experienced while reading Respectable: That those who find themselves growing up in the heart of their class rarely have to give their social location a second thought because everyone surrounding them reaffirms the same set of values; they never have cause to doubt nor need to reflect upon the intrinsic merit of their own class habitus (they are “working class and proud of it” or else they are “born to rule,” the “creme de la creme” as one of my schoolfriends – the son of two teachers – put it before going off to work for Lehman’s and DeutscheBank). For other specific class fractions, however – those on the boundaries between two classes, those who have moved between classes (up or down) – class becomes an obsession. Indeed, it is fair to say that this obsession with class and the concern with self-worth are in themselves part of the habitus of these particular class fractions; these are the benighted folk who comprise what may be called the “anxious classes,” that part of the middle class worried about falling into poverty, those upwardly mobile from the working class concerned about keeping up appearances, and those who engage in conspicuous consumption, the nouveaux riches, keen to demonstrate their social mobility. And, of course, Sociologists! It is class as these groups experience it, which is to say, self-consciously, that is really at the heart of Hanley’s book. Not that the book is any the worse for that. The arguments and observations are well supported, making good use of the canonical texts in the Sociology of Class (Paul Willis, Wilmott & Young, Pierre Bourdieu, etc.). But because it uses Hanley’s own experiences anecdotally as a way of introducing topics, it really only provides a phenomenology of the class migrant’s experience of class. Those who have spent their entire lives within their own class may have an entirely different view of class than that described here.

Hanley expresses her admiration for Richard Hoggart’s mid-20th-century classic The Uses of Literacy and to some extent has succeeded in producing a 21st-century version. While this is admirable, it means the book is accompanied by all the attendant vices of Hoggart’s book, particularly the tendency to wander off-topic for the sake of enumerating or recording particular events. Nonetheless, I found very little to disagree with and much to like, within the confines of the account she provides. It would have been interesting to have heard the voices of the people Hanley left behind in her movement between classes. Did they all fail to make it into the middle class? Are any of them better off financially than she is, and if so, how come? What is their view of class? We don’t know. What Hanley has really given us are the pathologies of a particular way of thinking about class, and the reader may conclude that the importance she ascribes to issue is nothing more than the result of her own upbringing. I’m inclined to agree. For a more comprehensive measure of the role and importance of class, I would suggest the need to add a macroscopic perspective, such as that provided by Pickett and Wilkinson’s The Spirit Level, as well as a historical dimension, such as that given in Conor McCabe’s The Sins of the Fathers. Which is not to say that Hanley’s book is not illuminating and a joy to read, only that vignettes, however beautifully and intelligently drawn, are only windows into a life, not maps of an entire world.

Respectable: The Experience of Class, by Lynsey Hanley. 2016. 240 pp. Allen Lane.

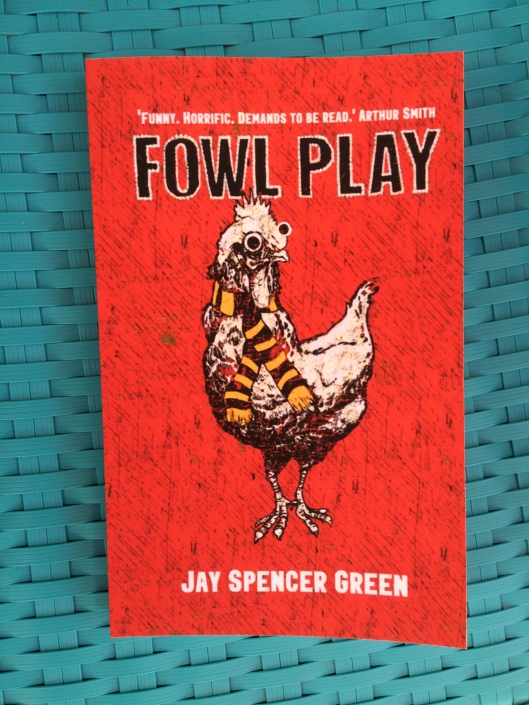

Best Indie Comedy 2018

Best Indie Comedy 2018

A thing of beauty is a joy forever. A Jay Spencer Green novel, by contrast, will haunt your dreams like an abusive waiter.

A thing of beauty is a joy forever. A Jay Spencer Green novel, by contrast, will haunt your dreams like an abusive waiter. I would like to welcome our first literary character to the Interview chair. Stumpy Sue is the awesome 11 year old hacker chick from the novel Fowl Play by Jay Spencer Green, You can see my review of this book

I would like to welcome our first literary character to the Interview chair. Stumpy Sue is the awesome 11 year old hacker chick from the novel Fowl Play by Jay Spencer Green, You can see my review of this book